Complicity

I’m willing to bet you’ve heard some version of the phrase, “100 companies are responsible for 71% of global carbon emissions.” This figure came from a 2017 CDP Carbon Majors Report, and frequent misinterpretations and misquoting aside, it has been a double-edged sword in the climate discourse.

On one hand, institutions have been trying to shirk the blame for climate change on to individuals for decades. Tactics range from fossil fuel company BP using public relations professionals to coin and popularize the term “carbon footprint” and creating an online calculator for you to calculate your personal carbon footprint, to the Macron government’s proposal that people should save energy by limiting the number of funny emails you send to friends (Merci Macron, that’s super duper useful). The popularity of the CDP report opened many people’s eyes to corporations’ responsibility for climate change.

On the other hand, this knowledge has led to climate inaction and ennui, particularly with the younger generations, many of whom believe there is nothing to be done about climate change. They see the ways that fossil fuels have been built into the fabric of society. They see that they do not even have a choice of whether to use fossil fuels due to, for example, car-centric infrastructure, gas heaters and stoves in their (rented) homes, and the endless single-use plastic around every single product. With the rising costs of living, the only things some can afford are products that are known to be the result of environmental and human exploitation, so it feels hopeless to change this system and useless to try to do anything in their personal lives when these gigantic corporations are negating individual efforts at scale.

I say all of this with confidence because I, too, bought into this idea for a while, and I sometimes return to this place after a particularly bad doomscroll. This is why I have always hoped to become a leader of a company someday, so that I can be one of the special people that wields real power to change things (naivité, perhaps). But recently, I read the book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer, and my thinking has shifted.

Kimmerer is a botanist and a member of the Citizen Potowatomi Nation. Through both the scientific lens and the lens of indigenous wisdom, she shows us that we need a “reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world.” One of the concepts she explains in her book is that of the Honorable Harvest, which is, in essence, the process of taking only that which is given by the Earth and, in reciprocity, giving back to the Earth. The existence of the honorable harvest implies the existence of the dishonorable harvest: greedily extracting as much as you can without giving anything back to the Earth. We can think of corporations today as participating in the dishonorable harvest, always drilling and mining and logging and manufacturing more and more and more, believing that there are no bounds to how much they can or should grow and never giving anything back to the Earth – this is the nature of our 71%.

However, Kimmerer writes, “it can be too easy to shift the burden of responsibility to the coal company or the land developers. What about me, the one who buys what they sell, who is complicit in the dishonorable harvest?” (p. 195) The truth is this: every single one of us bears the burden of climate change.

Loneliness

At the same time as our climate crisis, there is an epidemic of loneliness. This is not a coincidence.

The subject of third places has been hot in the discourse this year. Outside of work and the home, people need a “third place” to gather, but these third places are dwindling with the loss of brick-and-mortar establishments and public spaces. For most of us Americans, third places require a car to access, and most of the available third places are commercial establishments with rising amenity costs where money is a barrier to entry and, therefore, a barrier to friendship. The free, public spaces that do still exist like parks often have hostile architecture which prevents people from spending extended periods of time there. So, people stay home and experience the vast majority of their social lives via the internet where connection is both virtual and ephemeral.

In her video “third places, stanley cup mania, and the epidemic of loneliness,” YouTuber Mina Le talks about last year’s internet discourse over whether you should pick your friends up from the airport. Many people online argued that you should not be obligated to pick a friend up from the airport and that the traveler should, instead, take an Uber. Otherwise, the friend driving deserves payment. Le labels this as a lack of “generalized reciprocity,” and she argues that apps like Uber (and capitalism and productivity culture generally) have “made the act of helping transactional.” If you are sick, for example, it is uncouth to ask a friend to pick something up for you at the store or ask for help making meals – you should just order Instacart or UberEats. Le goes on to argue that this is a problem because we need these kind of interactions “to build solid friendships and to build trust in other people.” When we don’t engage, we further isolate ourselves. This is also why I am a skeptic of the metaverse and its contemporaries. I can appreciate the value of virtual reality in certain use-cases like gaming and training, but I am incredibly cautious of any attempt to push the experiences which would normally be a conduit for human connection (e.g., socializing, even shopping) further into the virtual space where it can be monitored and monetized, thus thinning our potential for connection to people and place.

So here we see the interconnection of community and reciprocity, or rather, the lack of community with the lack of reciprocity. We are cut off from community, and with this “dissolution of community,” as Kimmerer puts it, comes the disconnection from place and from responsibility to the land we occupy. It is not surprising that we do not feel the weight of climate change on our shoulders. We do not feel connected to each other nor to the Earth.

For Americans like me, the detachment from place began with the first European explorers. Kimmerer recounts the insights from her Native elders,

“After all these generations since Columbus, some of the wisest of Native elders still puzzle over the people who came to our shores. They look at the toll on the land and say, ‘The problem with these new people is that they don’t have both feet on the shore. One is still on the boat. They don’t seem to know whether they’re staying or not.’… can Americans, as a nation of immigrants, learn to live here as if we are staying? With both feet on the shore?”

(p. 207)

This question echoes in my head every time I see a travel blog on Instagram. In our culture, travel is not just a hobby, but lauded as an aspiration for everyone. These days, people dream of being digital nomads, although that is not only because it is trendy but also because it has become increasingly difficult to actually settle in one place (i.e., buying a house). Regardless, we ascribe more cultural value and status to traveling – constantly moving to collect and consume experiences without ever truly knowing and giving back to a place – than to staying in one place.

Speaking for myself, I have never felt responsible for the land I am on. Certainly not as a child in Texas, and as an adult, I have been moving around too much to ever get to know a place and its people (You can read my personal essay that was published in the Homeward zine on how I perceive my relationship to place as a third generation of immigrants). My husband and I made the decision to move to Seattle in 2023 because we wanted to put down roots. At the time, the concept of “putting down roots” to me meant buying a house, maybe raising a child – at a minimum, just not moving anymore. But since reading Braiding Sweetgrass, I feel this rooting more literally… maybe not literally… metaphysically. We are fortunate to have been able to purchase a house, and I have fallen in love with my neighborhood and my neighbors, human and non-human, which includes all the various mosses, ferns, and rhizomes I greet on the dog walks.

While non-indigenous Americans like myself might have been granted citizenship by the US government, we haven’t necessarily earned that citizenship from the land we inhabit. Kimmerer equates non-indigenous people to naturalized citizens. She says,

“Being naturalized to place means to live as if this is the land that feeds you, as if these are the streams from which you drink, that build your body and fill your spirit. To become naturalized is to know that your ancestors lie in this ground. Here you will give your gifts and meet your responsibilities. To become naturalized is to live as if your children’s future matters, to take care of the land as if our lives and the lives of all our relatives depend on it. Because they do.”

(p. 214-215)

And I do hope I can earn naturalization to this land over time. I am new here, and I am searching for ways to “give my gifts and meet my responsibilities.” So, how do we become naturalized to place?

Community

Community plays an important role in our relationship with the Earth. Kimmer writes,

“Some people equate sustainability with a diminished standard of living, but the aboriginal people of the coast old-growth forests were among the wealthiest in the world. Wise use and care for a huge variety of marine and forest resources, allowed them to avoid overexploiting any one of them while extraordinary art, science, and architecture flowered in their midst. Rather than to greed, prosperity here gave rise to the great potlach tradition in which material goods were ritually given away, a direct reflection of the generosity of the land to the people. Wealth meant having enough to give away, social status elevated by generosity.”

(p. 279-280)

Caring for the Earth is a group project. The indigenous people Kimmerer describes understood that they are part of the greater ecosystem of giving and receiving. Their existence and history disproves the doomerism that the world would be better off without humans. They nurtured the plants and animals that in turn sustained their lives. They never took more than they needed, and if one person had more than enough, they would share with their neighbor.

I swear I have heard this before… A-ha! My last article on degrowth economics! Is this what Timothée Parrique meant when he wrote that a degrowth economy would be “centered on needs and well-being” and would be an economy “where everyone is rich without anyone being poor”? While “degrowth economics” gives the impression of being a highly technical and innovative concept for white men in button downs and patagonia vests, it’s not really new. It is pointing toward the same ancient indigenous culture of reciprocity. Achieving a degrowth economy requires us to shift our perception of wealth away from the productivity culture that convinces us it is uneconomic to take a friend to the airport, to a reciprocity culture that encourages sharing our resources, time, and attention.

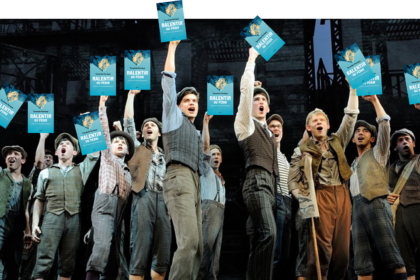

Community is both the antipode to loneliness and the tonic for abdication and climate nihilism. So, what does it mean to build community? I am afraid this is where my purported expertise ends because I, myself, am a novice at community building. For the first time in my adult life, I am actively seeking out ways to connect with those around me in my neighborhood and my city (I consider that college doesn’t count, as it is a controlled environment which presents you with ample opportunities to meet people, whether you want to or not). For me, much of that connection relies in art – museum exhibits, lectures with curators, talks by visiting authors, film screenings, local theater productions, gallery openings (I feel so fancy saying “gallery openings”). I also make a concerted effort to do things I’ll admit I never did much before such as volunteering with local mutual aid groups, engaging in protests and public comment sessions, and simply attending block parties to chat and swap plants and seeds.

Even my weekend chores are a meditation on community and place. Pepper the Pomeranian and I walk through the neighborhood, appreciating the flora, breathing in the Seattle air. It is so peculiar. I never paid attention to the air until I moved here. It smells like flowers and the ocean. I see my neighbors buzzing around the main street. I sign a petition. I buy some food for my unhoused neighbor; she likes chocolate and coffee with a lot of sugar. I ask my other neighbor if I can borrow her power drill. I eat a croissant from my local bakery. I buy vegetables at the farmers market. I don’t know how exactly I’ll use them, but I’m excited to figure it out. I am joyful knowing this food was grown and prepared by the hands of people I have met. I buy oranges, but there are too many, so I make orange pound cake and give it to my neighbors. In terms of saving the planet, it never feels like enough because it isn’t, but it is my beginning.

Power

After reading Braiding Sweetgrass, I planned to put the climate conversation to rest for a moment in order to focus on artificial intelligence. I picked up Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What is Human in a World of Machines by Dr. Joy Buolamwini. Buolamwini is one of the world’s leading researchers uncovering how AI reinforces oppressive structures like racism and sexism. The sentiments from Buolamwini’s final chapter felt familiar.

“We need your voice, because ultimately the choice about the kind of world we live in is up to us. We do not have to accept conditions and traditions that undermine our ability to have dignified lives. We do not have to sit idly by and watch the strides gained in liberation movements for racial equity, gender equality, workers’ rights, disability rights, immigrants, and so many others be undermined by a history of hasty adoption of artificial intelligence that promises efficiency but further automates inequality… Will we dare to believe in our individual and collective power?”

(p. 280-281)

Like the choice to accept or reject AI systems that undermine human dignity, we have a choice to accept the world as it is, to accept the dishonorable harvest. Kimmerer says that “We are all complicit. We’ve allowed the ‘market’ to define what we value so that the redefined common good seems to depend on profligate lifestyles that enrich the sellers while impoverishing the soul and the earth” (p. 307). I believe every decision is an opportunity to say, “No, I won’t comply” and to state your commitment to your values. Will we dare to believe in reciprocity and the honorable harvest?

Near the end of Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer recounts a night where she stood by the side of the road to help salamanders safely cross traffic. On this night, the US was also bombing Baghdad. She writes,

“The news makes me feel powerless. I can’t stop bombs from falling and I can’t stop cars from speeding down this road [killing crossing salamanders]. It is beyond my power. But I can pick up salamanders. For one night I want to clear my name. What is it that draws us to this lonely hollow? Maybe it is love, the same thing that draws the salamanders from under their logs. Or maybe we walked this road tonight in search of absolution.”

(p. 359)

Oh, how history repeats itself. Replace “Baghdad” with “Gaza,” and you can run the same story in 2024. Even though we may try to practice reciprocity, we are still complicit. We search for absolution, but it cannot be found. But that does not mean that we should give up and stop picking up salamanders from the road. Though far removed, we can choose to be in community with the people whose lives, families, homes, and ecosystems are being turned to rubble and ash. This is part of the climate crisis. This is part of our fight for human dignity.

So, what do we do? Something. We need to agree to do something. As Kimmerer says, “Despair is a paralysis… It blinds us to our own power and the power of the earth. Restoration is a powerful antidote to despair” (p. 328). Adopting the tenets of reciprocity and the honorable harvest and applying those to every decision is a starting framework. We can quite literally work to restore the land we are on, and we can also work to restore our connection to each other, to our values, to who we want to be.