Degrowth

Recently, I read the book Ralentir ou Périr : L’économie de la décroissance by Timothée Parrique, which translates to “Slow Down or Perish: The Economy of Degrowth”1. The book explains how capitalism is the root cause of the climate crisis and proposes new ideas for how to manage our economic system moving forward. The proposal can be summed up in a word: degrowth.

To me, the concept of degrowth is common sense. We know climate change is the result of our unmitigated pursuit of greater wealth, of unconstrained growth that began during the industrial revolution. We overproduce and overconsume, and as we do so, we emit carbon, deplete water sources, degrade soil, destroy habitats, throttle biodiversity, expel garbage… The list of the ways we rapidly extract from the Earth without replenishing is endless.

We make far more than we actually need, so the answer to mitigating environmental degradation would be to make less, to only make what we need and what promotes our well-being. That’s the key idea of degrowth. Parrique writes that,

“We must put the economy in degrowth to establish a stationary economy in harmony with nature where decisions are taken together and where wealth is equitably shared to be able to prosper without growth… A democratic economy where the decisions are informed by an ecological sympathy, where the production is centered on needs and well-being, where everyone is rich without anyone being poor. An economy whose aim would be a new form of prosperity — the quest for meaning and happiness in frugality and respect for the living.”1

Take this example: This week, my local news showed clips of people rushing to Target to get the latest limited edition Valentine’s Day Stanley cup. It begs the question “Why? What is all of this for?” Nobody needs these cups, but even if it is not a necessity for survival, does it promote people’s well-being and joie de vivre? Even within a degrowth economy, we can make things like art or other goods that bring pleasure, but I wonder whether Stanley cups actually fill this role. “You are paying $40 to join the hype,” writes Meredith Perkins for The Miami Student, “To carry the cool container. To be a part of the in-group,” even though they “will inevitably be replaced by the next-cooler-thing in six months.” The Cut reported this week that children and teenagers are even being bullied on the basis of not having a Stanley cup or – even worse – having a fake one. The satisfaction Stanley cups bring to an individual, the reason some of them buy so many cups, is mostly due to the hype and social status. Like makeup, skincare, and fast fashion trends, Stanley cups are the latest accessory being sold (primarily to women) at breakneck speed to fill a non-existent gap, a prime example of things we can live without, without sacrificing our well-being and comfort.

Fear

While degrowth is common sense and a beacon of hope in my eyes, it seems to spark fear in others. People fear that degrowth is a proposal to put the economy in recession (it isn’t) or that it is anti-innovation (it isn’t), but interestingly, the number-one criticism of degrowth that Parrique covers is that the word “degrowth” is unappealing. Other people propose words like “green economy,” but what does green economy even mean? Parrique asserts his support for the word “degrowth” because of its clarity: “The idea is there: produce and consume less. The term directly addresses the problem instead of sweeping it under the rug in the way of a positive economy, an economy of the common good, or a well-being economy.”1

I wasn’t necessarily surprised to read about this controversy. I live in the US and work in private industry; I know that economic growth is exalted as a virtue and some may feel that to question growth is sacrilege. But I was surprised – no, fatigued – to see a related article, “The Relentless Growth of Degrowth Economics” by Jessi Jezewska Stevens, cross my LinkedIn feed while I was in the midst of reading Parrique’s book

In the Foreign Policy Magazine article, Stevens recaps the Beyond Growth Conference hosted by the European Parliament in Zagreb, Croatia. The keynote speaker, Diana Ürge-Vorsatz, vice chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), provokes the audience composed largely of young people by asking them to, “Maybe consider a different word.” Stevens goes on to describe the proceeding reaction, “The suggestion to ‘find a better word,’ however, is met with an affronted laugh. For Europe’s young people, degrowth isn’t just a utopian slogan, but an intentionally provocative, environmental necessity—and an existing reality.”

Stevens also reports that Kohei Saito, a Japanese philosopher who has become famous for his book on “degrowth communism”, “doesn’t mind if others ‘use a different term’ than degrowth ‘as long as they’re willing to think outside of capitalism.'” Saito also noted “that using provocative language often serves an important purpose; degrowth was coined precisely to be unmarketable, with its founders anticipating the greenwashing that has befallen the likes of terms such as ‘sustainability,’ ‘green growth,’ and ‘carbon footprint.'”

So, why is the use of the word such a controversy? I can only speak to my experience, which is that I struggle to find the balance between being an authentic sustainability enthusiast / climate activist and a responsible representative of my company. I need to appeal to customers, investors, and future employees alike – though all these personas hold different perspectives on what a company should say and do regarding sustainability. I certainly fear saying the wrong thing, even (especially) while writing this very article. It is safer to be conservative with our language and easier to continue doing business as usual. It feels more pleasant to paint a picture of success (i.e., greenwashing) than to face hard truths head-on.

But I don’t believe it is radical to value the Earth and to value each other and to be honest about those values. People are tired of having the wool pulled over their eyes by climate deniers, and they are tired of the greenwashing – case in point: as of this week, European parliament banned “using terms including ‘environmentally friendly’, ‘biodegradable’, and ‘climate neutral’… in advertising or on packaging without concrete evidence.”

So, as far as “degrowth” goes, I’m going to say the word. I think we should not fear exploring and speaking about the possibilities of the future that include innovating our economic system.

Courage

At my company, courage is one of our four core corporate values (alongside care, curiosity, and collaboration). When these values were first announced to the employee-base, I did not understand why the company would need to tell us to exhibit basic human characteristics. (In the one-in-a-million chance our CEO is reading this, please don’t close the page! I’m sorry to have doubted you!) But the longer I work in the world of climate and corporate sustainability, I have come to understand that courage is not a given. We need to choose to swim against the current of business as usual if we want to make any real progress on climate, and we indeed need to be curious about new ideas for operating as a society (i.e., degrowth) and prioritize care for each other (especially those feeling the brunt of a warming planet).

In early 2023, I started volunteering with 350 Seattle on their Electrify Seattle campaign, the aim of which was to pass a Building Emission Performance Standard in Seattle that would require commercial buildings to electrify, reaching net zero emissions by 2050 while proving incremental progress starting in 2031. To be honest, I was a little scared to be volunteering. I was concerned that my association with an activist organization could be perceived as anti-business by some of my professional contacts. I was also doubtful that this group of grassroots organizers could win transformational legislation against the lobbying power of private companies, but in December 2023, we won. The collective action of everyday citizens won. This victory has slightly softened my jaded heart, and now I wonder if we may have fewer reasons to fear speaking honestly and directly about climate change than we may imagine. Everyday people want effective action on climate change, and when we have the courage to collaborate across industry, activism, and politics, we can achieve great things.

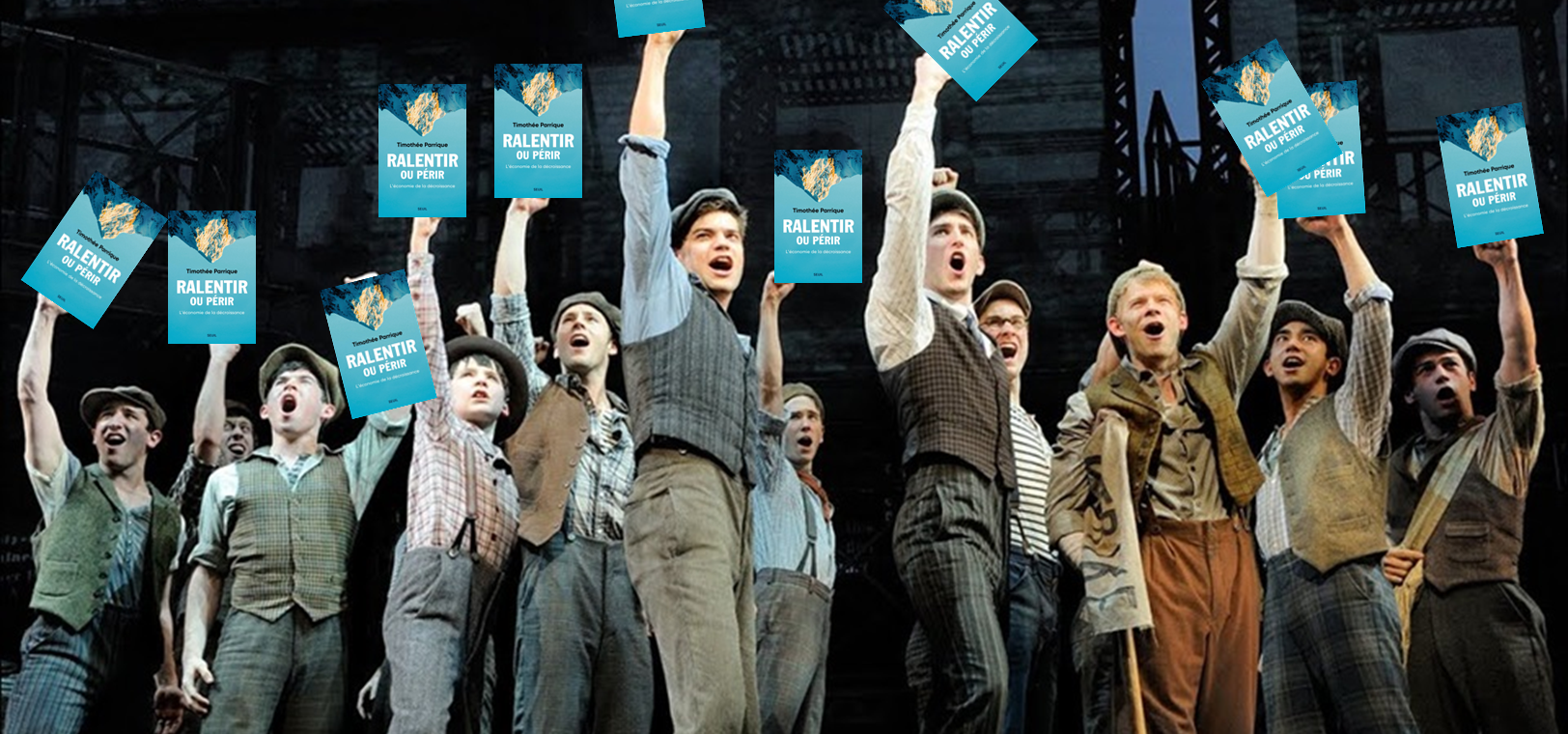

Since I am not a serious person, I will leave you with a quote that changed my life as a 17-year-old from the Broadway musical Newsies, “Courage does not erase our fears. Courage is when we face our fears.”

1 French to English translations of Ralentir ou Périr done by me. These may not be the same in the official English translation, expected to come out late 2024 / early 2025.

1st off— thank you for sharing. I look forward to reading the “official” translation. Please let me know when it becomes available.

2nd. From the perspective of an old fart about to retire, I believe at some point, unless things change dramatically in the US, it will become necessary to exit the institutional/industrial capitalistic system to be free to promote this vision. As long as profit, greed, and the love of power dominate our culture, the pressure to perpetuate that system will dampen our progress.

As one who lived through the 70’s, counterculture is not a dirty word. Right on!